Rock ‘n’ Roll Never Forgets

- Mariana Simioni

- 1 day ago

- 9 min read

The untold story of The Show Place, where a waterlogged disco became the stage for Metallica’s debut, the Ramones’ residency, and 15 years of hazy rock history. By Mariana Simioni Thanksgiving Eve, 1976. The line outside The Show Place began forming hours before showtime. First dozens, then hundreds, then a queue that stretched past the neon glow of the club’s dark windows, down the block, into the parking lot, where cars idled, and drivers craned their necks to see what was happening.

Another Pretty Face, a regional glam-rock band, was on the bill, a departure from the regular disco crowd.

Nothing special, the owners thought—just another Wednesday night.

By the time the band took the stage, more than 800 people had pushed through the door.

“It was unbelievable,” Wally Van Treek, a manager at the club who now lives in Lakewood, recalls nearly 50 years later. “Before that, if they had 100 people there, that’d be a lot. The owners looked at each other and said, ‘We have to change over to rock.’”

With that unexpected surge, the club at 347 South Salem Street in Victory Gardens—go-go bar by day, rock experiment by night—accidentally became one of the most unlikely incubators of Garden State rock history.

RISING FROM THE RUINS

The building Larry Gribler found in early 1975 had been closed for two years. Water damage was everywhere—a burst line had warped the floors beyond recognition. The heaters and air conditioning didn’t work. But buried beneath the wreckage was something unusual: a light-up Saturday Night Fever-style disco dance floor running down the center of the room.

Stephen Schiff, who now lives in Scotch Plains, and his brother, Ben, each owned a 25 percent stake in the club. Ben was a silent partner, but Stephen remembers his brother’s desperation in those early months. “Originally, he was looking for a liquor store, and I didn’t want a liquor store,” Stephen says. “I wanted a club.” They put a down payment on the building in March. “I had to borrow from my credit cards to give money to the realtor as my share.”

Gribler held 50 percent. “We worked basically day and night in there to get it into shape just so we could open up,” Schiff recalls. “We actually broke the lock to go in there and work.”

Somehow, they made it. “By June 1st, we actually opened up, which was amazing, because it was really in bad shape.”

They even got that light-up floor working again. The first weekend, they booked two major disco acts at $5,000 per night. “We lost money every day, every night,” Schiff says. “I had to borrow money from my parents to put in the registers.”

Victory Gardens in the mid-1970s was a working-class town with few pretensions and fewer entertainment options. The town didn’t want a go-go joint, but the owners needed daytime revenue to survive.

Schiff was desperate enough to follow a rumor about a local rock band drawing big crowds. “We booked Another Pretty Face, and we packed the place,” he says. The band became a twice-monthly booking. Within a year, they discovered that disco was dead, but loud guitars—and the kids who followed them—made the room come alive.

REINVINTING THE ROOM

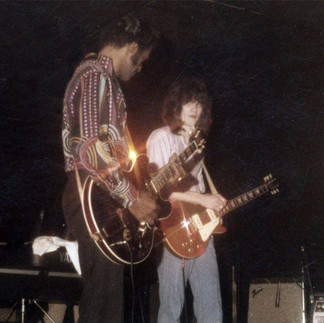

Later in 1976, The Show Place was in full transformation. Sound engineer Joe Berger redesigned the audio system, turning the modest stage into what performers would later describe as a “sonic powerhouse.”

“Everyone wanted to play there because they knew they’d get great sound,” Van Treek says. “It was state-of-the-art for 1976.”

Musicians who played The Show Place describe the same first impression: Dark. Dark walls, dark corners, dark in a way that seemed to absorb light and sound. “It was basically almost cut in two,” Schiff explains. “Go-go was during the day… in the front. In the back, we had a big stage.” Tables pushed right up to the stage. Two bars flanking the entrance and changing rooms tucked to the right behind plywood walls covered in graffiti.”

Today, many bands master their marketing before they master their music. That was hardly the case half a century ago. Van Treek admits that, while some memories are hazy, he is certain it was called The Show Place – even though decades of memorabilia reveal different spellings. All that mattered was getting the bands right.

Mark Redman was barely 18 when his band, Rapid Transit, began opening shows there in 1980. “We weren’t even allowed inside before 8 p.m.,” he remembers. “The club was a gentleman’s club until the dancers packed up and left.” When musicians finally arrived for load-in, they squeezed through the door into those plywood backstage rooms, stacking guitar cases and warming up before their set.

One of Redman's fondest memories was opening for Huey Lewis and the News—before anyone knew them by name. “There were four of us in Rapid Transit,” he says. “I really can’t remember too much, but I remember Huey sitting at the bar playing harmonica before load-in, having a drink, and relaxing.”

THE TALENT ARRIVES

After that Thanksgiving Eve in 1976, word spread among booking agents: This little club in Morris County could move serious numbers. When the drinking age was still 18, the young crowds were enormous—and surprisingly well-behaved. “We had absolutely no problems with these kids. Zero,” Schiff remembers. “They listened. They were very enthusiastic… grateful.”

It wasn’t long before the international acts started arriving—some legendary, others not yet known even to the bartenders pouring their drinks.

Leslie West of jam-band Mountain packed the place. Thin Lizzy came through when “The Boys Are Back in Town” still felt dangerous and new. Slade arrived, drawing a massive crowd and returned two months later to record portions of Slade Alive, Vol. 2 on that stage. Blackfoot became a regular draw. Roy Buchanan and Rory Gallagher both played there.

Then came punk.

“We did the Ramones a lot,” Schiff says. “My partner hated them… I loved them.” The band came back at least a dozen times, bringing along their inner circle—including Arturo Vega, the visual architect behind their iconic logo. The staff traded T-shirts with him.

One night, because The Show Place had run out of merchandise, Joey Ramone took the stage wearing a neon-green Swamp Water liquor shirt from behind the bar. Months later, Van Treek saw that same shirt printed in a rock merchandise catalog, selling for $40.

Blondie slipped in quietly before fame found them. “This artsy-looking couple asked me to play their single,” Van Treek says. “I didn’t know who they were. It was [Hawthorne native and Centenary College alum] Debbie Harry and Chris Stein.” Stephen also booked Talking Heads and Cheap Trick as they were rising through the ranks.

The bookings grew stranger, wilder, more improbable.

One night, Schiff heard a new album on the radio that stopped him in his tracks. “I listened to Bat Out of Hell, and I said to my partner, we got to get this band called Meat Loaf.” Schiff tracked down the band’s attorney and booked two nights at $5,000 each.

Then came the ice storm.

“It was this ice storm… horrendous,” Schiff recalls. “I’m wondering how much money we’re going to lose.” But when he looked outside, “there’s a line out front waiting to get in.” The storm was so severe they couldn’t fit everyone who wanted in—but they still packed 1,000 people across both nights. “Actually, the ice storm was a blessing because we couldn’t fit more people in.”

Years later, Schiff heard Meat Loaf tell an interviewer about his first gig. “He said… ‘It was some strip club in New Jersey.’ I just laughed.”

Rory Gallagher arrived with a contract that mandated a grand piano—so the staff borrowed one, lowered it into a pickup truck, and hauled it inside. After a blistering two-hour set, Gallagher sat alone at that piano, playing boogie-woogie for half an hour while his band packed their gear.

On April 16, 1983, heavy-metal icons Metallica stormed the stage with a new guitarist—Kirk Hammett—making The Showplace the site of his first-ever performance with the band. Hammett had joined just five days earlier, replacing Dave Mustaine, who was fired the same day Hammett auditioned in New York. The opening act that night was Anthrax’s original lineup. “Let’s put it this way,” Schiff says, “It was loud.”

Peter Bazzani, who worked and performed at The Show Place for years, remembers that night differently. “They were all drugged up and couldn’t play to save their lives,” he says. “After that, they went back to California, and they blew up.”

The punk band Dead Kennedys came through with a member whom Schiff won’t forget. “He had green hair, he was like 6-foot-5,” he recalls. The musician approached Schiff’s pregnant wife, Hindy, and asked if she’d remember him when he stepped out for a smoke. “She said, ‘Yeah, I think I’ll remember you.’”

And then there was Chuck Berry, who famously traveled without a band or crew. He drove himself to the club in a Cadillac, stepped out, and handed over a guitar case. “You had to supply everything—band, equipment, the works,” Van Treek says. “But every musician on earth knew his songs.”

Bazzani puts it simply: “If I told you who played there, you’d be blown away.”

The venue’s eclectic roster reflected the interconnected nature of the music world. “There were local, national, and international acts… and every major movement you can think of,” Bazzani recalls. “There’s so much interconnection in music—friends, bands, trade shows, tours—it’s all part of the story of The Show Place.”

DRINKING AGE WENT UP. ATTENDANCE DWINDLED.

In 1983, New Jersey raised its drinking age from 18 to 21, shutting out a generation of regulars overnight. “It was really a shame that they bumped it up to 21,” Schiff says. “We lost a lot of business… the 18-, 19- and 20-year-olds didn’t come in anymore.”

Thrash metal filled the calendar, but the crowds thinned. “A lot of people couldn’t come anymore,” Van Treek says. “A lot of clubs around here closed after the drinking age went up.”

The Show Place stopped booking bands in the 1990s. Schiff had learned a valuable lesson about survival in the volatile music industry. “There’s always going to be recessions and boom-bust type things,” he says. “You have to have an income that smooths everything out. Luckily, my wife had a good job.” Hindy worked in the pharmaceutical industry, eventually becoming a senior vice president. “Make sure your wife has a good job… especially in the music business.”

The last band Schiff ever booked was the Good Rats. After that, the performance room was converted into a state-of-the-art recording studio in partnership with engineer Ben Elliott. They soundproofed half the building while keeping go-go in the other half.

REBUILDING AS A STUDIO

“Ben was the house engineer for 35 years or so,” Bazzani recalls. The studio attracted serious talent. Eric Clapton showed up. Keith Richards came in and recorded a song. They even produced a compilation album.

The studio operated for roughly 20 years. When Elliott passed away on April 5, 2020, the music finally stopped. Later that year, COVID-19 delivered the final blow. “You can’t really do go-go with COVID,” Schiff explains. “You can’t have guys around the bar with masks, drinking.” After 45 years, he was ready. “I was planning on retiring anyway.”

Larry Gribler, who had found that waterlogged building back in 1975 and transformed it into something improbable, passed away on October 11, 2019.

Today, the building serves an entirely different mission as the Victory Gardens headquarters of nourish.NJ, a nonprofit food pantry and social services organization. Yet traces of its past still surface in conversation.

“We hear it from some of the people who come here for our services,” says Chief Operating Officer of nourish.NJ Dave Bein. “A lot of long-time residents remember it from the many versions of this building. No one really talks about coming here when it was a gentleman’s club—but they definitely talk about remembering bands coming through here back in the ’70s and ’80s.”

“It used to be the world-class Show Place nightclub and recording studio,” Bazzani reflects. “It’s almost like nothing is left. Nobody would even know if you looked at it.”

“We lost a lot,” Van Treek says quietly. Much of his memorabilia—signed albums from the Ramones, Jack Bruce, Blackfoot—was destroyed in Superstorm Sandy. “But the memories, you know—you keep those.”

There was nothing glamorous about The Show Place. It was dark and a little strange, embracing its split personality. The walls absorbed spilled beer and the graffiti of a thousand bands who came and went. And it boasts a proud legacy in the hazy memories of rock fans, many of whom reminisce on a Facebook page called “The Show Place For Rock.”

“There’s too much history there to let it just go by the wayside,” Bazzani says.

It was dark. It was loud. And for nearly 15 years, it was a portal: a place where the world’s biggest names brushed up against a town that turned out to be more ready for them than anyone realized.

As Van Treek puts it, with the kind of understatement that defined the era: “Just meeting and partying with the people in the bands… that was the coolest part.“

Comments